Einar Thorsteinn

Art Vent Letting the Fresh Air In

November 2, 2008

I arrived home Friday night to a New York that was one giant Halloween party, with exceptionally warm weather that led to a certain sartorial minimalism; I’m guessing there’s not a single pair of fishnet hose left to buy in the city. By contrast Chelsea yesterday was like a ghost town. The galleries were manned by skeleton crews, and I wasn’t surprised when one dealer admitted to me that nothing was selling. In my overfilled inbox, however, was a press release from Sperone Westwater announcing their move in December to a nine-story, 20,000 SF. Norman Foster-designed gallery one block north of the New Museum on the Bowery, so someone’s optimistic.

I’d hoped that my ten days away just before the election would provide some much-needed respite from agonizing over it every single moment, but instead I found the Europeans equally obsessed. To judge by the amount of coverage the election is getting in the British press, you’d think it was a local event. And the international members of Olafur Eliasson’s staff, who I joined for lunch in his Berlin studio, were as up-to-date on Joe the Plumber and the price of Sarah Palin’s wardrobe as anyone. It feels as if the whole world is holding its breath.

There’s even a Web site started by three Icelanders, If the World Could Vote, which (as of this writing) has collected 666,246 symbolic votes from 210 countries: 578,461 (86.8%) for Obama, 87,780 (13.2%) for McCain. I’d feel better if the polls reflected a similar disparity.

Our purpose in going to Olafur’s studio was to shoot footage for a short documentary focusing on his collaboration with mathematician, architect, and all-around visionary Einar Thorsteinn, who previously worked with Buckminster Fuller and Linus Pauling. Olafur and Einar have been working together since they met in Iceland 12 years ago, when Olafur, then 29, was looking for someone to help him build a geodesic dome-type structure, and one project led to another. The two-hour shoot couldn’t have gone better. We had some anxiety when, in the morning, city workers suddenly appeared with deafeningly noisy equipment to spend several hours pounding gravel into the cobblestone courtyard outside, but miraculously they finished just as we were about begin. I barely had to refer to my list of prepared questions; Olafur and Einar addressed each point in order as methodically as if they’d been clued in by a secret spy (I believe in never sharing questions with interviewees in advance, lest I get a canned response).

I’d hoped that my ten days away just before the election would provide some much-needed respite from agonizing over it every single moment, but instead I found the Europeans equally obsessed. To judge by the amount of coverage the election is getting in the British press, you’d think it was a local event. And the international members of Olafur Eliasson’s staff, who I joined for lunch in his Berlin studio, were as up-to-date on Joe the Plumber and the price of Sarah Palin’s wardrobe as anyone. It feels as if the whole world is holding its breath.

There’s even a Web site started by three Icelanders, If the World Could Vote, which (as of this writing) has collected 666,246 symbolic votes from 210 countries: 578,461 (86.8%) for Obama, 87,780 (13.2%) for McCain. I’d feel better if the polls reflected a similar disparity.

Our purpose in going to Olafur’s studio was to shoot footage for a short documentary focusing on his collaboration with mathematician, architect, and all-around visionary Einar Thorsteinn, who previously worked with Buckminster Fuller and Linus Pauling. Olafur and Einar have been working together since they met in Iceland 12 years ago, when Olafur, then 29, was looking for someone to help him build a geodesic dome-type structure, and one project led to another. The two-hour shoot couldn’t have gone better. We had some anxiety when, in the morning, city workers suddenly appeared with deafeningly noisy equipment to spend several hours pounding gravel into the cobblestone courtyard outside, but miraculously they finished just as we were about begin. I barely had to refer to my list of prepared questions; Olafur and Einar addressed each point in order as methodically as if they’d been clued in by a secret spy (I believe in never sharing questions with interviewees in advance, lest I get a canned response).

Despite requests by collectors and institutions to buy individual models and even the whole, Olafur and Einar’s Model Room, much of which was at PS 1 for the MoMA show, has been reinstalled in the conference room of the new studio and spills out into the hallway, where it continues to grow and serve as inspiration for new projects. The attitude toward it is hardly precious—this is a workshop, Einar said—and he told us, while we were filming it, to feel free to move things around as we liked. While Terry and Erica were setting up, I had time to spend with these quirky geometric gems, which led me to think about the relationship between harmony and chaos and how, to be fully engaging, an artwork requires certain degrees of each. It was also energizing to be around the 30 or 40 members of Olafur’s busy team, who he sees as working with rather than for him, acknowledged co-creators, an attitude which results in a palpable enthusiasm all around. He also feeds them well. Every day the cook (working in the studio kitchen, which is not walled off, so that she’s part of the creative bustle around her) prepares a simple, healthy lunch—the day I was there it was pumpkin risotto with a green salad and great bread. The food is is laid out buffet style and eaten on long trestle tables in the cavernous dining area, which has walls and high ceilings faced with the remnants of beautiful old tiles and tall, arched windows. As well as making sure everyone gets proper nutrition, the communal meal has its practical reasons for being—no one wastes time going out for food, and it provides a daily opportunity for cross-communication that would be unlikely otherwise.

Despite requests by collectors and institutions to buy individual models and even the whole, Olafur and Einar’s Model Room, much of which was at PS 1 for the MoMA show, has been reinstalled in the conference room of the new studio and spills out into the hallway, where it continues to grow and serve as inspiration for new projects. The attitude toward it is hardly precious—this is a workshop, Einar said—and he told us, while we were filming it, to feel free to move things around as we liked. While Terry and Erica were setting up, I had time to spend with these quirky geometric gems, which led me to think about the relationship between harmony and chaos and how, to be fully engaging, an artwork requires certain degrees of each. It was also energizing to be around the 30 or 40 members of Olafur’s busy team, who he sees as working with rather than for him, acknowledged co-creators, an attitude which results in a palpable enthusiasm all around. He also feeds them well. Every day the cook (working in the studio kitchen, which is not walled off, so that she’s part of the creative bustle around her) prepares a simple, healthy lunch—the day I was there it was pumpkin risotto with a green salad and great bread. The food is is laid out buffet style and eaten on long trestle tables in the cavernous dining area, which has walls and high ceilings faced with the remnants of beautiful old tiles and tall, arched windows. As well as making sure everyone gets proper nutrition, the communal meal has its practical reasons for being—no one wastes time going out for food, and it provides a daily opportunity for cross-communication that would be unlikely otherwise.

The 30,000 SF building, which the studio only recently moved in to, is a red brick fortress-like former brewery, and when Einar told me about it last year, referring to it as Olafur’s “castle in the center of Berlin,” I didn’t know that he was being so literal. The first floor is the kitchen, workshop and showroom (in the old studio, one worker told me, there was no room even to set things up and see how they looked), the second is the conference room and studio, and the top floor will house a school for 15-20 students (best described in this That experience, coupled with a visit to Einar and Manuela’s home in the Berlin outskirts, a house which nearly bursts with the results of their combined creativity (the subject of the next Art Vent House Report), made me want to just come home and work. The best possible outcome.

The 30,000 SF building, which the studio only recently moved in to, is a red brick fortress-like former brewery, and when Einar told me about it last year, referring to it as Olafur’s “castle in the center of Berlin,” I didn’t know that he was being so literal. The first floor is the kitchen, workshop and showroom (in the old studio, one worker told me, there was no room even to set things up and see how they looked), the second is the conference room and studio, and the top floor will house a school for 15-20 students (best described in this That experience, coupled with a visit to Einar and Manuela’s home in the Berlin outskirts, a house which nearly bursts with the results of their combined creativity (the subject of the next Art Vent House Report), made me want to just come home and work. The best possible outcome. I didn’t see much to mention in London, other than Frank Gehry’s pavilion at the Serpentine, which looked as if he’d handed the project over to an intern. Or perhaps it would have been better if he had. Terry deemed it “over-built and under-designed.” While the press release described it as “seemingly random,” I—a Gehry fan in general—couldn’t discern any over-arching concept, but saw it as an example of chaos that could have benefited from a little mediating harmony. I think we’ve had enough random for one century, thank you. While we were there an English girl and her Indian boy friend—art students, no doubt—were in the middle of an argument about their relationship when the guy became distracted and, looking over at the pavilion, muttered, “That thing is a pile of shit.”

I did, however, get to spend quality time with the Upholstery Eater and am pleased to report that she’s thriving despite (or maybe because of) her inherited proclivity.

I did, however, get to spend quality time with the Upholstery Eater and am pleased to report that she’s thriving despite (or maybe because of) her inherited proclivity.

Comments (3)

October 19, 2008

Yesterday I drove my “Obamamobile” as a friend calls it—blue car + bumper sticker + magnet—to Boston and back, as well as a bit around Waltham and Framingham, and was surprised to note hardly any—actually no—other sign that there’s a major heated political campaign going on. Maybe no one bothers because Massachusetts is considered a foregone conclusion. However here in the Berkshires—the third bluest county in the nation after Manhattan and Brooklyn—we take every opportunity to show support.

And I’m off to Europe early Tuesday morning for almost two weeks—to England and then Berlin to work (with Terry Perk and Erica Spizz) on a short film about Olafur Eliasson and Einar Thorsteinn’s collaborative process, funded by the University for the Creative Arts in the U.K. I don’t know if the trip will prompt more posts, fewer posts, or no posts, so bear with me. Cheerio!

And I’m off to Europe early Tuesday morning for almost two weeks—to England and then Berlin to work (with Terry Perk and Erica Spizz) on a short film about Olafur Eliasson and Einar Thorsteinn’s collaborative process, funded by the University for the Creative Arts in the U.K. I don’t know if the trip will prompt more posts, fewer posts, or no posts, so bear with me. Cheerio!

Olafur Eliasson and Einar Thorsteinn, details from The Model Room, as installed at PS 1 last spring,.

Olafur Eliasson and Einar Thorsteinn, details from The Model Room, as installed at PS 1 last spring,. June 3, 2008

I hardly ever recall my dreams, but when I do they’re almost always the same. Except for the ones where I’m in a public place without my clothes, or suddenly remember I have a kitten or baby I’ve forgotten to take care of (they’re always okay, I just feel this terrible guilt), all of my dreams are travel dreams where I can’t get somewhere, can’t find my luggage, etc. I thought when that dream finally came true that I wouldn’t have it anymore but that didn’t happen (yes, I really was in the airport outside Reykjavik at 6:30 a.m., unable to find Einar’s phone number or my luggage, running across the tundra after the only bus of the day that was leaving without me…). In last night’s dream I was lurching from car to car on a futuristic train trying to find my luggage, clutching a gigantic zip-lock plastic bag stuffed with hundreds of tiny bottles of toiletries to my chest. The “stewardesses,” all in a gaggle talking about their dates of the night before, were no help. At one point I found myself walking through the empty observation car as we were passing Niagara Falls and next to the rushing water was a giant screen duplicating the scene, as if it were a rock concert. All of this was no doubt triggered by reading an article in an old (April 28) TIME magazine, about Richard Branson and his revolutionary plans for Virgin Airlines (where I’m a regular), one of which is to end the “Sisyphean tyranny of the cart” by offering choices (which you pay for, of course) from a computer screen, brought to you whenever you want. Wow, I think, what a great idea, until I realize that if I did get that plastic-wrapped $12 turkey sandwich, most likely it wouldn’t be appetizing enough to eat, so what to do with it? Perhaps use it as a neck support as I nap, hoping I won’t dream.

P.S. The Iceland story ended happily. Einar, sensing something was up, rang me, I found my luggage, and the beautiful blond bus dispatcher took it upon herself to arrange for a driver to take me to Einar’s outpost, about 25 minutes away (cost: $16)—where breakfast was waiting. It was almost worth it to find out how caring people could be to a stranded stranger in a far-flung place.

P.S. The Iceland story ended happily. Einar, sensing something was up, rang me, I found my luggage, and the beautiful blond bus dispatcher took it upon herself to arrange for a driver to take me to Einar’s outpost, about 25 minutes away (cost: $16)—where breakfast was waiting. It was almost worth it to find out how caring people could be to a stranded stranger in a far-flung place.

Photo: Carol Diehl, Iceland 2006

April 28, 2008

Le mur vegetal, Musee du Quai Branly. (Photo: Julie Ardery)

Le mur vegetal, Musee du Quai Branly. (Photo: Julie Ardery)I know I'm not supposed to like Jean Nouvel's Musee du Quai Branly just as I'm not supposed to like Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim, but for different reasons. Still, I like both, for different reasons, and one of the best parts of the Musee du Quai Branly for me is the "vertical garden" on the facade of the section of the museum that houses staff offices and the way it provides a transition to the neighboring buildings. Now I find out that it's the work of one Patrick Blanc [via C-Monster] who specializes in putting greenery on the face of buildings. Here's my friend Einar Thorsteinn's contribution to the genre:

Iceland, 2006 (Photo: Carol Diehl)

More about vertical gardens in "Green Anchors" in the NY Times.

December 4, 2007

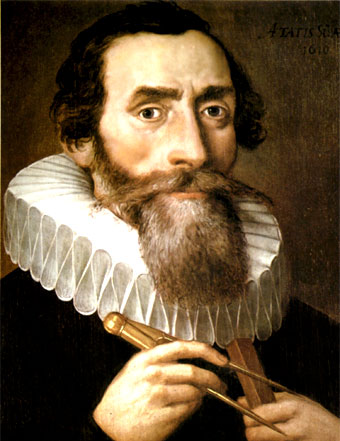

More from my friend, Einar (click label below for other posts), here with his newest configuration. He tells me a few (around 14) stars or stellated polyhedrons are known in geometry, the earliest being those of German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630).

Einar first discovered Kepler's stars in the Kepler Museum in Weil der Stadt, Germany in 1973. That, along with meeting Buckminster Fuller in 1975, was the beginning of his involvement with geometry. When I asked how long this project took he said, "I've been working on geometry since 1973 and cannot figure out how much of this third of a century it took to finally define the Thorsteinn Star. Maybe it was the fine Brieselang air..." -- referring to the village outside Berlin where he and Manuela live.

I wanted to know more, and when I looked up Kepler I found this image, which I suggested to Einar looked a lot like him. True, Kepler's nose is much longer, as Einar immediately pointed out, and his eyes are brown, not blue. But what I see isn't a superficial commonality as much as a mischievous glint in the eye and look of deep inner satisfaction.

For more information on stellation and facetting, Einar suggests Guy Inchbald’s website: www.steelpillow.com/polyhedra/StelFacet/history.html.

November 27, 2007

There are people in the world who spend much of their time conjuring up geometric forms no one has used before. One such person is my previously-mentioned friend, Einar Thorsteinn, whose configurations often appear in Olafur Eliasson’s work. Einar just sent me these photos (click to enlarge) of himself in Olafur’s studio, working with one of his latest, which has the working title of “MoMA Joint” because it’s intended for use in Olafur’s upcoming survey exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Einar suggests that the stackable form can have other, more practical applications, such as being cast in concrete for the walls of a house, where the openings could become windows.

There are people in the world who spend much of their time conjuring up geometric forms no one has used before. One such person is my previously-mentioned friend, Einar Thorsteinn, whose configurations often appear in Olafur Eliasson’s work. Einar just sent me these photos (click to enlarge) of himself in Olafur’s studio, working with one of his latest, which has the working title of “MoMA Joint” because it’s intended for use in Olafur’s upcoming survey exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Einar suggests that the stackable form can have other, more practical applications, such as being cast in concrete for the walls of a house, where the openings could become windows. The level of rigor Einar contributes to Olafur's work was what I found lacking in the wire sculptures in Antony Gormley’s recent show at Sean Kelly (up through December 1st). I want to like Gormley’s work because I’ve never forgotten the first piece I saw of his in 1991--entitled Field, it consisted of 35,000 handmade clay figures assembled on the gallery floor, all of whom seemed to be beseeching me. With overtones of war and poverty—even though those issues weren’t addressed directly, or perhaps because they weren’t—it was quite moving.

However these current sculptures of Gormley's seem rather lackadaisical--as if they haven't made up their minds whether to be tight and geometric or loose and organic, but hover uncomfortably in-between--and his glassed-in room filled with steam needs some additonal aspect to make it more than....a glassed-in room filled with steam. It’s a lot of technology for not a lot of impact. When an artist puts that much effort and expense into building something, our expectations rise accordingly—whereas Robert Irwin gets a lot more mileage out of a mere piece of scrim.

Gormley:

Irwin:

September 19, 2007

September 5th was the opening of Olafur Eliasson’s mid-career survey at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and I wasn’t there, mostly because I couldn’t bear to leave my little corner of Berkshire heaven. I’m not ready for the art world season to start, not just yet. God was, and is, rewarding us with the most fabulous weather and I’m convinced no art or art-related event could match the perfection of an early evening dip in the cool and tranquil Green River. Besides, Einar and Manuela came here on their way back to Iceland and then Berlin, with a full report.

Olafur, I predict, is on his way to establishing himself as a household name, and when the show travels to the Museum of Modern Art and P.S. 1 in April, and later the Dallas Museum of Art, I’ll be curious to see how he handles the media blitz that’s sure to follow. Up until now, he’s managed to remain aloof and keep the emphasis focused on the art—with the exception of Cynthia Zarin’s profile in The New Yorker (November 13, 2006--not yet available online).

Zarin is a New Yorker staff writer, and it seemed as if she didn’t have a sufficient art background and did little research, depending almost entirely on her interviews for information. A friend’s comment was “When you’re an expert, you always find something wrong” but I disagree. I mean, this is The New Yorker, which I expect to query the experts or, at the very least, read what’s been written about the subject. Because I thought of The New Yorker as a standard, discovering that it was fallible was a crisis of faith, like that moment in childhood when you first discover your parents could be wrong. The worst part was that this jumble of mis-emphasis and misinformation was held together with a gloss of the sharp and engaging writing for which The New Yorker is justly renowned, but which I now see as simply style. For instance Zarin absolutely nailed it when she described Olafur as having, “the slightly crumpled look of a shop teacher at a progressive school” but treated the work itself as nothing more than a by-product of his personality.

This was the gist of my letter to the magazine, which was not published:

To the editor:

Because I feel the magazine and its readers are capable of looking at issues in depth, I was sorry that the profile by Cynthia Zarin about the artist Olafur Eliasson concentrated on his personality and process rather than the art and the philosophy behind it—and without sufficient description of the art, you have no idea why such attention is being given to it. It is especially necessary in the case of Eliasson’s work because, since most of his work is temporary and not reproducible, the number of people who have actually seen it is small.

Zarin mentions Eliasson’s relationship to the artists “Robert Irwin and James Turrell and the idea of ‘seeing yourself seeing’” but does not explain this concept or describe how it plays out in the actual work. Later she notes that Eliasson was “deeply affected by the work of the phenomenologist philosophers, especially Edmund Husserl—with their emphasis on the individual experience of reality—and by Lawrence Wechsler’s biography of Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees—without going into any greater detail or telling us what it was about the Wechsler book that so affected Eliasson. The questions Eliasson is seen asking himself are presented more as musings than essential to an overarching philosophical inquiry.

In discussing Eliasson’s Weather Project at the Tate Modern, Zarin does not mention how, in the wake of its extraordinary success, the Tate wanted to extend its run and Eliasson refused—an act that, given the artist’s consuming interest in the context of art, including that which comes before and after its installation—can be considered as much a part of the piece as its mist, mirrors, and light.

Zarin makes a case for differentiating Eliasson from his predecessors Irwin and Turrell by stating that, “Like them, he is interested in light, to which he adds a preoccupation with what he calls ‘the intersection of nature, science, and human perception.’” She goes on to say that “unlike those artists, who tend to draw the viewer’s attention to natural phenomena—Turrell’s ‘sky spaces, for example, showcase the open sky—Eliasson consistently uses mechanical artifice to create his effects….” This is absolutely not true. The work of Irwin and Turrell pioneered this “intersection of nature, science, and human perception,” making it possible for Eliasson to expand upon it, which Eliasson fully acknowledges. Further, Irwin and Turrell have done plenty of work using only mechanical means (the effect of light on scrim, to name just one example), just as Eliasson is equally involved in working with natural phenomena—as seen in a later paragraph where he says, “I want to plant flowering trees around the pool. For one week in May the petals will drop and cover the water.”

In an art world short on meaningful dialogue, where personality and process often masquerade as art, the subject of Olafur Eliasson and his work offers a unique opportunity to marry the personal with the profound and present a significant discussion on the nature of art. Since I’m sure it will be a long while before Eliasson’s work is again discussed so thoroughly in these pages, I regret that the opportunity was missed.

Sincerely,

Carol Diehl

How can you write about Robert Irwin and not be aware of his scrim pieces? Or, for that matter, about Eliasson and not know he'd turned rivers green? I could have gone on, to comment on how Zarin says, “Eliasson invites comparison to Buckminster Fuller, with whom he shares an interest in the aesthetics and the utility of mathematic forms,” without saying where this influence comes from: his collaboration with Einar Thorsteinn, who was Fuller’s protégé. Although the stamp of Einar’s geometry is visible throughout Olafur’s work and they frequently share exhibition credit, Einar was not available for an interview when Zarin visited the studio...so he goes unmentioned? Not that Einar minded; he often says he likes “being famous for not being famous.” But it skews the picture to leave him out of an article that’s almost entirely about Olafur’s collaborative process.

There’s more but I’ll stop. If the article had been written by Calvin Tomkins (author of Duchamp, one of the best art biographies ever) or Peter Schjeldahl (who doesn’t write profiles, but if he did…) I’d be jealous. But that’s how I want to feel when I read The New Yorker.

There. At least I’ve gotten this one off my chest, where it’s been sitting since November. Too bad I didn’t have a blog then, so I could have responded in the moment. And to read a spot-on critique of another New Yorker article (on Paul McCartney, who seems to be showing up in all of my posts, and I haven’t even heard his new album), along with a riveting exchange with its author, go to http://restrictedview.blogspot.com/2007/06/you-wont-see-me.html.

Olafur, I predict, is on his way to establishing himself as a household name, and when the show travels to the Museum of Modern Art and P.S. 1 in April, and later the Dallas Museum of Art, I’ll be curious to see how he handles the media blitz that’s sure to follow. Up until now, he’s managed to remain aloof and keep the emphasis focused on the art—with the exception of Cynthia Zarin’s profile in The New Yorker (November 13, 2006--not yet available online).

Zarin is a New Yorker staff writer, and it seemed as if she didn’t have a sufficient art background and did little research, depending almost entirely on her interviews for information. A friend’s comment was “When you’re an expert, you always find something wrong” but I disagree. I mean, this is The New Yorker, which I expect to query the experts or, at the very least, read what’s been written about the subject. Because I thought of The New Yorker as a standard, discovering that it was fallible was a crisis of faith, like that moment in childhood when you first discover your parents could be wrong. The worst part was that this jumble of mis-emphasis and misinformation was held together with a gloss of the sharp and engaging writing for which The New Yorker is justly renowned, but which I now see as simply style. For instance Zarin absolutely nailed it when she described Olafur as having, “the slightly crumpled look of a shop teacher at a progressive school” but treated the work itself as nothing more than a by-product of his personality.

This was the gist of my letter to the magazine, which was not published:

To the editor:

Because I feel the magazine and its readers are capable of looking at issues in depth, I was sorry that the profile by Cynthia Zarin about the artist Olafur Eliasson concentrated on his personality and process rather than the art and the philosophy behind it—and without sufficient description of the art, you have no idea why such attention is being given to it. It is especially necessary in the case of Eliasson’s work because, since most of his work is temporary and not reproducible, the number of people who have actually seen it is small.

Zarin mentions Eliasson’s relationship to the artists “Robert Irwin and James Turrell and the idea of ‘seeing yourself seeing’” but does not explain this concept or describe how it plays out in the actual work. Later she notes that Eliasson was “deeply affected by the work of the phenomenologist philosophers, especially Edmund Husserl—with their emphasis on the individual experience of reality—and by Lawrence Wechsler’s biography of Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees—without going into any greater detail or telling us what it was about the Wechsler book that so affected Eliasson. The questions Eliasson is seen asking himself are presented more as musings than essential to an overarching philosophical inquiry.

In discussing Eliasson’s Weather Project at the Tate Modern, Zarin does not mention how, in the wake of its extraordinary success, the Tate wanted to extend its run and Eliasson refused—an act that, given the artist’s consuming interest in the context of art, including that which comes before and after its installation—can be considered as much a part of the piece as its mist, mirrors, and light.

Zarin makes a case for differentiating Eliasson from his predecessors Irwin and Turrell by stating that, “Like them, he is interested in light, to which he adds a preoccupation with what he calls ‘the intersection of nature, science, and human perception.’” She goes on to say that “unlike those artists, who tend to draw the viewer’s attention to natural phenomena—Turrell’s ‘sky spaces, for example, showcase the open sky—Eliasson consistently uses mechanical artifice to create his effects….” This is absolutely not true. The work of Irwin and Turrell pioneered this “intersection of nature, science, and human perception,” making it possible for Eliasson to expand upon it, which Eliasson fully acknowledges. Further, Irwin and Turrell have done plenty of work using only mechanical means (the effect of light on scrim, to name just one example), just as Eliasson is equally involved in working with natural phenomena—as seen in a later paragraph where he says, “I want to plant flowering trees around the pool. For one week in May the petals will drop and cover the water.”

In an art world short on meaningful dialogue, where personality and process often masquerade as art, the subject of Olafur Eliasson and his work offers a unique opportunity to marry the personal with the profound and present a significant discussion on the nature of art. Since I’m sure it will be a long while before Eliasson’s work is again discussed so thoroughly in these pages, I regret that the opportunity was missed.

Sincerely,

Carol Diehl

How can you write about Robert Irwin and not be aware of his scrim pieces? Or, for that matter, about Eliasson and not know he'd turned rivers green? I could have gone on, to comment on how Zarin says, “Eliasson invites comparison to Buckminster Fuller, with whom he shares an interest in the aesthetics and the utility of mathematic forms,” without saying where this influence comes from: his collaboration with Einar Thorsteinn, who was Fuller’s protégé. Although the stamp of Einar’s geometry is visible throughout Olafur’s work and they frequently share exhibition credit, Einar was not available for an interview when Zarin visited the studio...so he goes unmentioned? Not that Einar minded; he often says he likes “being famous for not being famous.” But it skews the picture to leave him out of an article that’s almost entirely about Olafur’s collaborative process.

There’s more but I’ll stop. If the article had been written by Calvin Tomkins (author of Duchamp, one of the best art biographies ever) or Peter Schjeldahl (who doesn’t write profiles, but if he did…) I’d be jealous. But that’s how I want to feel when I read The New Yorker.

There. At least I’ve gotten this one off my chest, where it’s been sitting since November. Too bad I didn’t have a blog then, so I could have responded in the moment. And to read a spot-on critique of another New Yorker article (on Paul McCartney, who seems to be showing up in all of my posts, and I haven’t even heard his new album), along with a riveting exchange with its author, go to http://restrictedview.blogspot.com/2007/06/you-wont-see-me.html.

July 6, 2007

When I wrote the post below, I assumed that the siding on the house inside the dome was not wood but metal, like that on so many of the houses in Iceland where wood is scarce. Einar wrote to correct me, adding this bit of Icelandic humor: "What do you do when you get lost in the Icelandic woods? Stand up."