Kehinde Wiley

Art Vent Letting the Fresh Air In

April 9, 2012

I just finished writing my review for Art in America of the Kehinde Wiley exhibition at the Jewish Museum, The World Stage: Israel (to be published sometime during the run of the show, which is on through July 29th). I’ve been interested in Wiley’s work for some time, and in 2008, commissioned from him a portrait of Obama for the cover of TIME which, sadly, never ran.

However what I love about this exhibition is the totality of the experience: the paintings in the context of Wiley’s selection of examples of antique papercuts and textiles from the museum’s collection, and the grand, historic Fifth Avenue mansion that houses it. I began to think about how frustrated I’ve become with the white-box gallery format, so sterile and one-dimensional it rarely shows art to advantage—like staging a fashion show in a hospital. However, uncharacteristically, I don’t have an answer to the problem. Most “designed” museum exhibitions are even worse. Like Jorge Pardo’s installation of Pre-Columbian art at LACMA, they always seem to be in competition with the art they’re showcasing. The Tod Williams and Billy Tsien design for the 2008 Louise Nevelson show, again at the Jewish Museum, stands out as the best I’ve seen. Probably I’ve never gotten over seeing a stunning Pop Art show, many years ago, in the baroque multi-balconied atrium of the Palazzo Grassiin Venice (including a 20-foot high Warhol Mao), where the contrast and interplay of old and new showed both to exciting advantage. That’s what happens here as Wiley’s hip-hop sensibility is set off against the cased antiques and the wood-paneled opulence of the museum’s interior.

Photos: Bradford Robotham/The Jewish Museum.

Doing my research I read “The Diaspora is Remixed,” Martha Schwendener’s review in The New York Times. As I remember, she’s written other pieces that didn’t raise my hackles (or you would have heard about it!). This one, however, is marked with surprising vitriol, as if there’s a subtext we’re not getting.

….the show raises some difficult questions. For instance, what is the position of the Ethiopian Jew in Israeli society? The gallery installation gives the impression of Jewish culture as a seamless visual narrative, slipping faultlessly from old Europe to modern-day Tel Aviv. It also posits, particularly in a video accompanying the paintings, Israel as a haven for persecuted Ethiopian Jews.

First, I question if it’s fair to critique an artist on the basis of the success or failure of his presumed intention, rather than on the work itself. Secondly, what is it about the “gallery installation” that gives the impression of Jewish culture as a seamless visual narrative? The fact that Wiley’s paintings are shown alongside works from the museum’s collection? If that’s what Schwendener is referring to, my understanding is that the antique objects are part of the exhibition because Wiley was inspired by such patterns and it provided an unusual opportunity for the museum to display them. To see it as an attempt to rewrite history is a stretch worthy of Fox News.

Also, in the video where Wiley’s subjects talk about their lives in Israel, it’s about not being fully accepted. As for Israel being a “haven,” maybe it is, all things being relative. Perhaps being discriminated against is better than being persecuted.

By not mentioning the others, Schwendener gives the impression that Wiley has focused solely on Ethiopian Jews, when they’re only a third of his subjects. The rest are dark-skinned native-born Israelis and Arab Israelis—who, no one can say, have had an easy time of it. On the hand-carved frames Wiley designed for the Arab Israelis, inscribed in Hebrew, is Rodney King’s famous cry, “Why can’t we all get along?” The point made in the video is that hip-hop and reggae have brought these spurned groups together; the music scene is the “haven” where all are accepted.

Another question is why Mr. Wiley’s work focuses solely on young men, when many of the textiles on view were made by women, and, as the catalog informs us, one of the best-known Israelis of Ethiopian descent is a female singer named Hagit Yaso, who won last year’s edition of an Israeli show similar to “American Idol.”

My answer to that, which is the only answer to why any artist does anything, is because he wants to. Why didn’t de Kooning paint men? Because he didn’t want to. (Has anyone even asked that question?) Are we obligated to be equal-opportunity artists, presenting society as society would prefer? However if it must be discussed, Wiley has explained that his initial impulse came from having seen, in his childhood, portraits in museums of men who didn’t look like him—which could have little to do with painting women, regardless of the fact that….

Part of the answer is that Mr. Wiley has generally painted preening young men, and there is a strong homoerotic element in his work that is glossed over here.

Gasp, Wiley is gay! I don’t know who’s glossing it over, since he’s hardly in the closet. Is it mandatory to discuss in depth an artist’s sexual orientation at every turn? (Or rather a “gay” artist’s orientation, since the same does not apply to straight artists.) Should the Jewish Museum, in their promotional material, be faulted for not making a bigger deal of it?

And finally….

Just as music critics have complained of hip-hop’s becoming a corporatized global commodity, Mr. Wiley can be accused of using it to neutralize differences and difficulties….And it is those very difficulties that we rely on art to broach.

[This when, a few paragraphs back, she writes, “the show raises some difficult questions.”]

Regardless, I never thought art had a responsibility (to whom?) to broach differences and difficulties. (I’m becoming more and more grateful that I’m an abstract painter.) Further, by highlighting the “disenfranchised” (Schwendener’s word, BTW) in a way that enables them to be seen and empowered as individuals, it would seem Wiley is doing just that. It’s not Wiley who is somehow using hip-hop to “neutralize”—i.e. make it seem as if differences don’t exist. His work celebrates a vibrant global community that does not recognize racial distinctions thereby, quite literally, neutralizing the differences—which can only be a good thing.

Everything Schwendener criticizes Wiley for avoiding, he seems to have provoked her into discussing. In other words, his art has made her think about and explore the very issues she is critiquing him for lacking—by her own criteria, Wiley has succeeded!

It seems that unless black artists approach their subject matter in a thoroughly predictable, heavy-handed and didactic manner, they’re not doing their job, are not “political” enough—and apparently poor Wiley has the double burden of not being gay enough either.

A gay black artist—especially one who gets involved with anything having to do with Israel—just can’t do anything right.

Note: The rumor that Wiley himself does not actually paint his paintings, that they’re farmed out to workers in China, is perpetuated by Schwendener when she says that they look “factory-produced.” In the interest of thoroughness, I called his gallery, who told me that although Wiley does, like many artists, have assistants who may help with the intricate backgrounds, but he alone is responsible for the central figures. Not that I care, one way or the other. They are beautifully painted and the marginally mass-produced look relates to the intention, like images on postage stamps, posters depicting African potentates—or covers of TIME Magazine. More about his process here.

Comments (7)

September 28, 2009

Last Friday night was the first installment of this season’s monthly Review Panel at the National Academy Museum, a series that consistently ranks among the few not-boring art panels in the history of the Universe. This time, as usual, moderator David Cohen stirred the pot, while panelists David Carrier, David Brody, and the razor-sharp Linda Nochlin (whose feminism, with her insistence on the word “germinal” rather than “seminal,” has not flagged) weighed in on four current gallery exhibitions: Maya Lin, Chris Ofili, Kehinde Wiley, and Janine Antoni.

Kehinde Wiley, After John Raphael Smith's A Bacchante after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 2009, Photograph, 31 5/8 x 39"

Kehinde Wiley, After John Raphael Smith's A Bacchante after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 2009, Photograph, 31 5/8 x 39"

The last two contained examples of “art about art”: Most of Kehinde Wiley’s photographs are examples of young Black hip-hop guys in the same pose as famous women from art history (odd that no one mentioned Robert Colescott here), and Janine Antoni’s refers to, among other things, Louise Bourgeois’s multiplicitous spiders.

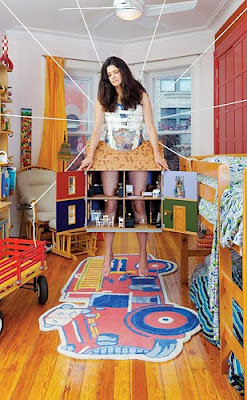

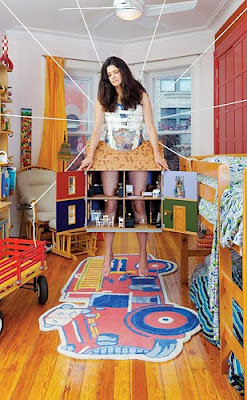

Janine Antoni, Inhabit, 2008, Digital C-print, 116 ½ x 72”.

Janine Antoni, Inhabit, 2008, Digital C-print, 116 ½ x 72”.

You know my stance on wall text (so can imagine my reaction when David Carrier said he didn’t fully grasp the Wiley paintings without the labels) but have I ranted sufficiently about how utterly lame I think most “art about art” is? Especially when it devolves, like the Antoni piece, into a game of “Find That Reference.”

I want to see art that’s powerful enough to keep me in the experience all on its own, not as a comment on something else, and not something that I have to bring extraneous information to—such as the “artist’s intention”—in order to “get” it.

Or, to put it another way, reference to other art, or anything outside the work itself, triggers an intellectual response that can get in the way of an emotional one. It offers only one interpretation, which makes for a closed circuit, rather than serving as a stimulus to the viewer’s imagination and opening it up to myriad possibilities.

“Art about art” is a lose/lose situation: if artists are better than those they reference, the citation only drags them to a lower level—and if they’re not as good (somewhere I think I used the example of David Salle’s paintings after Chardin) then all the viewer can think about (after “Oh yeah, Chardin”) is how they’d rather be looking at the original..

Uh, except maybe in this case…

Kehinde Wiley, After Jean-Bernard Restout's Sleep, 2009, Photograph, 30 5/8 x 49 1/8"

Kehinde Wiley, After Jean-Bernard Restout's Sleep, 2009, Photograph, 30 5/8 x 49 1/8"

Kehinde Wiley, After John Raphael Smith's A Bacchante after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 2009, Photograph, 31 5/8 x 39"

Kehinde Wiley, After John Raphael Smith's A Bacchante after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 2009, Photograph, 31 5/8 x 39"The last two contained examples of “art about art”: Most of Kehinde Wiley’s photographs are examples of young Black hip-hop guys in the same pose as famous women from art history (odd that no one mentioned Robert Colescott here), and Janine Antoni’s refers to, among other things, Louise Bourgeois’s multiplicitous spiders.

Janine Antoni, Inhabit, 2008, Digital C-print, 116 ½ x 72”.

Janine Antoni, Inhabit, 2008, Digital C-print, 116 ½ x 72”.You know my stance on wall text (so can imagine my reaction when David Carrier said he didn’t fully grasp the Wiley paintings without the labels) but have I ranted sufficiently about how utterly lame I think most “art about art” is? Especially when it devolves, like the Antoni piece, into a game of “Find That Reference.”

I want to see art that’s powerful enough to keep me in the experience all on its own, not as a comment on something else, and not something that I have to bring extraneous information to—such as the “artist’s intention”—in order to “get” it.

Or, to put it another way, reference to other art, or anything outside the work itself, triggers an intellectual response that can get in the way of an emotional one. It offers only one interpretation, which makes for a closed circuit, rather than serving as a stimulus to the viewer’s imagination and opening it up to myriad possibilities.

“Art about art” is a lose/lose situation: if artists are better than those they reference, the citation only drags them to a lower level—and if they’re not as good (somewhere I think I used the example of David Salle’s paintings after Chardin) then all the viewer can think about (after “Oh yeah, Chardin”) is how they’d rather be looking at the original..

Uh, except maybe in this case…

Kehinde Wiley, After Jean-Bernard Restout's Sleep, 2009, Photograph, 30 5/8 x 49 1/8"

Kehinde Wiley, After Jean-Bernard Restout's Sleep, 2009, Photograph, 30 5/8 x 49 1/8"